Demystifying ‘diets’

Where to start

The paleo diet, Slimming World, alternate-day fasting, juice cleanses…

You get the idea. Diets can be an absolute minefield.

Many of you have met patients with type 2 diabetes who are frustrated by the amount of conflicting dietary advice out there. Clinicians, too, can often feel just as perplexed as the people they are supposed to be treating. NICE [NG28] advocates for ‘individualised and ongoing nutritional advice’ but it is often criticised for its lack of clarity.

The goal of this article is not to endorse one strategy over another but to simplify how diets work so that clinicians feel confident enough to apply the concepts flexibly according to each patient’s unique needs and preferences. While lifestyle advice should be holistic, this article will focus solely on the dietary aspect of managing type 2 diabetes.

There are many paths to success

The Tour de France is a professional cycling competition made up of varying stages. No rider has ever won the entire Tour by beating their competitors in every stage outright – instead, they find victory by excelling in the races that best suit their abilities.

Sprinters are often muscular and perform well on flat terrain with their explosive speed. Climbers, with their lightweight frames and exceptional cardiovascular endurance, thrive in mountain stages. Time triallists can keep aerodynamic positions and steady paces over long distances without the aid of a peloton’s slipstream. There are also rouleurs, or all-rounders, who show versatility across disciplines.

Just like the Tour de France, there are many paths to success when managing type 2 diabetes. The key for all of them is consistency and adherence to the chosen method, as all diets can lead to improved metabolic health when executed diligently.

The three fundamental principles of every ‘diet’

As outlined by Dr Peter Attia in his book ‘Outlive’, the mechanisms of every diet can be distilled into three fundamental principles. Regardless of how complicated they may seem; all diets work by modifying at least one of these three parameters:

1: Caloric Restriction

‘How much you eat’

This is the concept of intentionally having fewer calories than the body needs to create a deficit. Think portion control and calorie counting.

Caloric restriction is effective and allows flexibility with food choices. It is often used by bodybuilders and athletes for rapid weight loss, but long-term adherence can be challenging due to increased hunger and cravings. While it can be burdensome to meticulously track calories, improvements in technology and smartphone apps have made this easier.

Professor Roy Taylor’s research showed a link between liver fat accumulation and the progression of type 2 diabetes. His studies demonstrated that a very-low calorie diet (VLCD) significantly reduces liver fat and blood sugar. The DiRECT study then implemented this plan on a larger scale and found that 46% of type 2 diabetic patients who followed the prescribed weight management program achieved normal HbA1c levels. In the extension phase of the study, 13% of the participants who continued to receive support remained in remission five years later. VLCDs are not typically recommended for long-term use due to their restrictive nature and should be conducted under close medical supervision.

2: Dietary Restriction:

‘What you eat’

This involves the deliberate reduction or elimination of specific food groups from the diet. Keto, vegan and low-fat diets are all examples of this.

This framework allows for diets that can be customised to address specific concerns, like reducing sugar to manage type 2 diabetes. Eliminating carbohydrates can also reduce food cravings. Personal responses to dietary restriction can vary. Avoiding certain food groups may lead to nutritional deficiencies and it can be difficult to follow in social settings due to limited food choices. Overloading is still possible; for instance, a strict plant-based diet made up entirely of processed foods can still negatively affect one’s energy balance.

Dr David Unwin has shown that 46% of the type 2 diabetic patients in his practice who adopted a low-carb lifestyle achieved drug-free remission and 93% of those with prediabetes attained normal HbA1c levels. Although it’s argued that a low-carb diet is too difficult to maintain long-term, there is growing evidence to support its effectiveness for sustained remission. It is essential for patients and clinicians to plan this diet together, as its effect on blood sugar may require medication changes.

3: Time Restriction

‘When you eat’

This entails limiting meals to specific times. It can include daily time restricted feeding as in 16/8, alternate-day fasting or periodic fasting like the 5:2 method.

This technique can be easy to adopt because it often aligns with naturally existing mealtime habits, making the transition smoother. While time restriction is straightforward and allows for a variety of foods, there is the potential to overindulge or ‘binge’ within the given time window. Additionally, the lack of protein during fasting periods can cause muscle loss.

Dr Michael Mosley is often credited with popularising the 5:2 diet and the Fast 800 plan in the United Kingdom. Research on intermittent fasting is still evolving, with some studies showing its benefits in managing type 2 diabetes. Lots of studies on time-restricted eating have been done on animal models, making it hard to draw definitive conclusions on their effects in humans. Given the variability in patient responses, it is important that diabetics consult a healthcare professional to tailor fasting protocols to their specific health needs and conditions.

Ignoring these principles

As already mentioned, this article does not intend to champion any dietary intervention over another. However, one message needs to be made plain and clear: ignoring all three of these principles is harmful. Consuming as much as you like, of whatever you like, whenever you like, will eventually result in poor health over time.

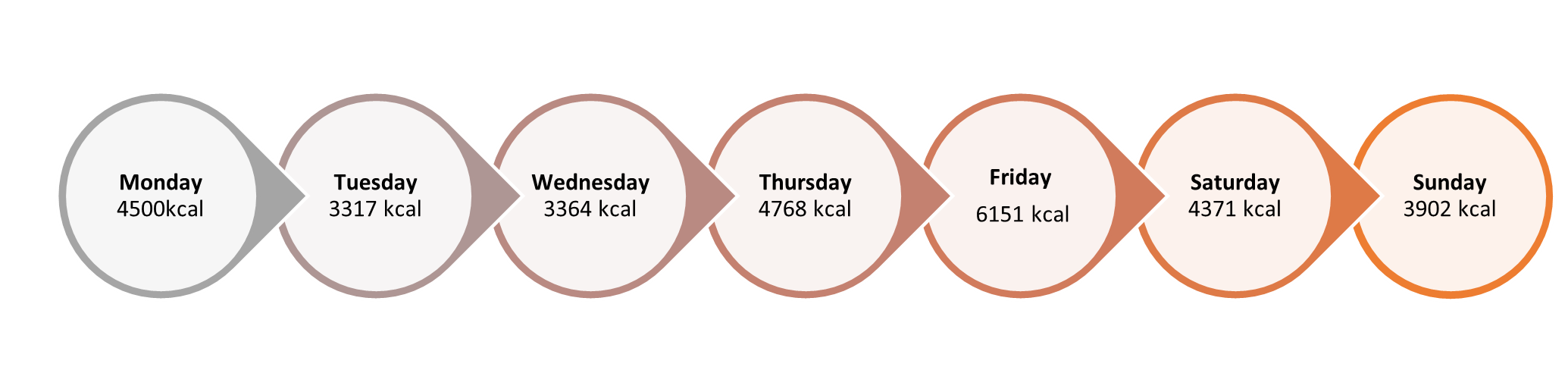

Inspired by Dr Chris van Tulleken’s book ‘Ultra Processed People’, last year I spent a week eating as much of whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted. Here are the results:

Hitting a daily average of 4,339 calories, I hugely exceeded the UK’s current recommendations for men and women - 2,500kcal and 2,000kcal, respectively. This is a stark reminder that carefree eating over time will invite repercussions, especially since ultra-processed food or ‘junk food’ is so prevalent in our current food landscape. Ultra-processed foods often deliver too many calories, too quickly, in a way that our digestive systems had not evolved to process. The prioritisation of eating ‘real food’ serves as a natural buffer against this.

Do not ignore protein

Proteins are often called the ‘building blocks of life’ because of their foundational role in biological structures. Adequate protein intake is essential for building and keeping muscle mass – a core defence against conditions like type 2 diabetes, as skeletal muscle is a primary site for glucose utilisation in our bodies. Time-restricted diets may not deliver enough protein and could potentially lead to muscle loss. Studies show that distributing protein throughout the day optimises absorption compared to having it all in one large meal.

Contrary to widespread belief, eating too much protein is not that dangerous. Most healthy kidneys are very efficient at excreting the surplus, making overdose unlikely. Having said that, people living with chronic kidney conditions or inborn errors of protein metabolism should consult a healthcare professional before making significant changes to the amount of protein they eat.

Protein contributes to a feeling of fullness by suppressing the release of ghrelin, a hormone that usually triggers hunger. These satiating effects can therefore help prevent overeating other food groups.

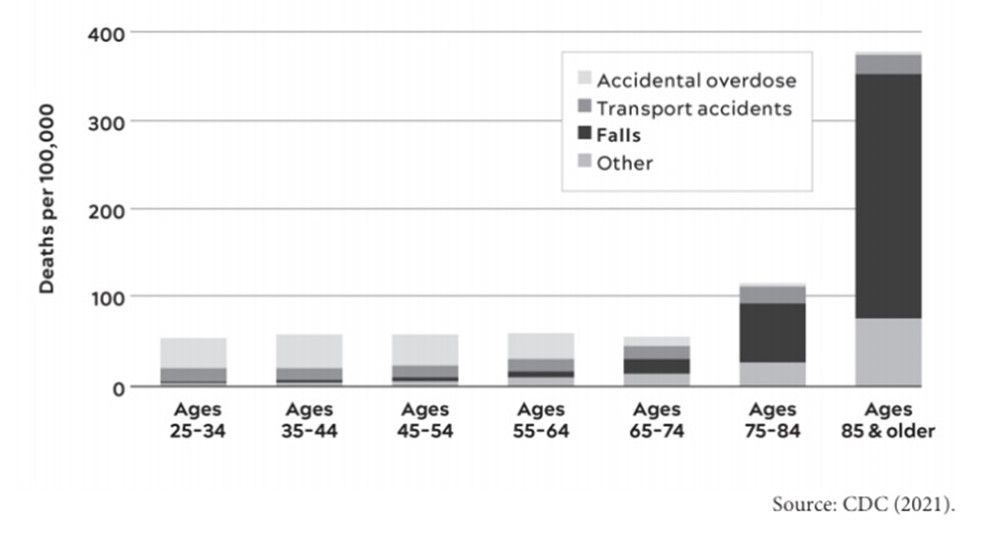

Maintaining muscle becomes increasingly critical when we age as it helps mitigate the risk of falls. This chart by the CDC gives some insight into just how dangerous falls are in the later years of life.

Do not ignore protein, it is a vital nutrient that should not be overlooked, especially the older we get.

Our role as clinicians

Navigating the world of diets can be daunting for patients and clinicians alike but this becomes less overwhelming when we recognise that every diet relies on manipulating three main principles. Whether reducing the total amount of calories, dropping specific food groups or adhering to time-restricting eating, patients can manage and potentially reverse type 2 diabetes.

It bears repeating that ignoring all three of these principles – eating as much of whatever you like, whenever you like - is a guaranteed path to metabolic disruption in our modern food environment. An emphasis on ‘real food’ over ultra-processed alternatives provides a natural safeguard against eating too many calories. The value of protein cannot be overstated either; apart from when medically contraindicated, maximising its uptake is crucial for good health, particularly as we age.

Our role as clinicians is akin to that of a cycling coach at the Tour de France. Rather than promoting a one-size-fits-all solution, we can collaborate with our patients to identify their specific needs, strengths and preferences. By doing this, we can empower them to map their own individual paths to success. Finding the most suitable approach is important, as outcomes rely heavily on consistency and adherence.

Sidenote: It is always worth considering whether a patient has a genuine carbohydrate or sugar addiction, as addressing this may require a more direct course of action like cutting out carbohydrates altogether if moderation is not possible. This assessment tool helps figure out whether your patients meet the criteria.

By demystifying diets and focusing on the three fundamental principles that they share, we can better manage type 2 diabetes and encourage long-term health.

By Jack Smith

Jack Smith has held various professional roles within healthcare, most recently working as a clinical Pharmacist for West Knowsley PCN. He is passionate about addressing diabetes through improved patient education, behaviour change and the upskilling of clinicians.

If you would like to contribute to future newsletters or the wider event programme, please get in touch at dpcenquiries@closerstillmedia.com

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

.png/fit-in/1280x9999/filters:no_upscale())

)

)